Logan Maxwell Hagege is the first living artist to be featured on the cover on Western Art Collector Magazine — and not just their artwork. The cover features the painting “A Song at Sunset,” Hagege’s largest multi-figure painting to date, 96”x144”.

Glenn Dean Print Release

We are happy to announce Glenn Dean’s first ever print edition release, “Equilibrium.” The print will be released exclusively through our online shop on Sunday May 31st, 2020 at 10am PT

(www.maxwellalexandergallery.com/shop)

Title: “Equilibrium”

Image size: 19 3/4” x 25”

Paper size: 22” x 27”

Edition of 300

Signed and numbered by the artist.

Gallery Emboss Stamped.

A portion of proceeds will go to Feeding America’s Covid-19 Response Fund.

International shipping is available.

For questions, please contact us at info@maxwellalexandergallery.com

Western Art Collector Six Page Article on Brett Allen Johnson's "Essential Desert" Exhibit

VIEW WORKS FROM THE SOLO EXHIBITION, DESER ESSENTIAL, HERE.

Transcending Forms Brett Allen Johnson’s newest work at Maxwell Alexander Gallery pushes and pulls at the fabric between realism and abstraction. By Michael Clawson

The Italian painter Giorgio Morandi was a still life painter in the early 20th century who worked with an assemblage of models that included all the “usual suspects”—subjects such as a vase with a fluted neck, ceramic pitcher with large handle, tall narrow bottle, coffee cup, square bottle with wavy neck and an elusive teacup. Morandi would line his subjects up and paint them. When he was done, he would mix them up and paint them again under different light or different groupings. He did hundreds of these paintings, if not thousands. He would title every single one Natura morta, Italian for “dead nature,” the term used for still life.

Morandi’s name doesn’t come up a lot in Western circles, but he comes up when talking with Utah painter Brett Allen Johnson, who admires Morandi’s passion for his subjects. Where Morandi had bottles, vases and ceramic cups, Johnson has sandstone cliff faces, rocky spires jutting out from desert soil, vast mesas with white walls, and mountains creased

with shadows. Johnson has taken these key geologic components of the desert and filled his paintings with different combinations of them, as well as other subjects such as adobe buildings, massive cloud formations, cattle skulls, cowboys on horseback and cattle pens. The result is a stunning cross section of the Southwest from one of Western art’s rising new stars, who will be having a major new solo show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery starting on September 7.

“I paint my landscapes with a still life sensibility. I like the broad shapes and smooth surfaces. Most of my landscapes are not filled with an exceptional amount of vegetation, mostly because I’m really focusing on these big shapes that showcase the very best of this clear light we have here in the Southwest,” Johnson says. “I use a lot of photography when I’m gathering research. In fact I have a really expensive catalog of photos at this point, but when I get back to the studio I tend to paint more from memory, just really cropping in close so I can focus on the essential part of the painting. I like to distill things down to just the parts I want to show.”

This distillation of form yields stunning results in his color and composition. He pulls detail out of the picture and focuses on the shapes, and how they interact with the light, and, in turn, his pictures tend to have an abstract feel to them—a sort of Maynard Dixon meets Ed Mell mashup—that pushes and pulls against abstraction and realism. But even that aspect has some wiggle room: are these abstract paintings of reality, or realism rendered from nature that has abstract qualities? Johnson leaves room for both interpretations with his marvelous new paintings, works such as Ode to Arizona, with its red rock hills and layers of exposed strata, and Of Stone and Sand, which shows white-washed cliffs under a cobalt blue sky. “When I hear people say my work feels abstract, it does feel so validating. I don’t do a bunch of dropped edges or angular stuff, but I use abstraction to internalize the big shapes. I just see these big forms and want to recreate them in a unique way,” he says. “I don’t want to look at something and transcribe the shape. I want to get in deep and close and kind of conceptualize the best parts of it, which is why I draw from memory or imagination, that way I can really take something and rebuild it from the ground up.” Johnson arrived to this point by spending time outdoors in the desert. A lot of time.

After high school, the artist enrolled in a graphic design program at a nearby community college, but then quickly realized that he wanted to paint. In 2005 he dropped out and hit the road. “All my early trips were nearby, just so I could see what was out there to paint. If you go just west of me it looks a lot like the Great Basin—real flat and lots of sagebrush. Later I would end up in southern Utah and Arizona. I would go down to hike and I realized I loved those big solid forms and the strong light,” he says. “You could really make an impactful painting with these huge forms, but I wanted to not only paint these big subjects but help people understand how they could be shown in a painting, how their size could be worked into a piece. It was fun looking for those subjects.”

He kept at it and improved. By 2016, Beau Alexander, owner of Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles, had seen his work and reached out. “Beau somehow stumbled onto some of my work on Instagram. I only had just a few followers then, and by no means was doing consistently good work. I guess he saw some potential, and he contacted me to see what I was doing. I had always been told to pick a local gallery for my first one, to avoid all the shipping expenses and associated hassles, but that was pretty much my dream gallery, so there’s no way I wasn’t gonna jump,” Johnson says. “It was my first experience with any gallery, and nothing I gave him sold at first, but he was patient. He’s always interested in the big picture. Honestly, he’s been the best thing I could ever have hoped for, an ally and confidante, a gentle coach and a friend. And he has a shared vision: that Western art has a lot of innovation left to give, that the West is a special place and it’s still relevant in the 21st century. Beau is the man.”

The gallery also brought Johnson into a unique fold of talent, including some of the top Western artists working: Logan Maxwell Hagege, Glenn Dean, Mark Maggiori, Jeremy Lipking, Eric Bowman and others. These young artists are carving their own path within Western art, and doing it on their own terms.

For Johnson’s newest works, the artist is taking classic views of the West and re-imagining them in his own abstracted- realist fusion of ideas. Consider In the Land of Mesas, with its massive rock formation that stands with shaded cliffs facing the viewer. The cliff face has been rendered in flat panels, almost like sheets of drywall plastered directly into the landscape. A layer of lighter-colored rock runs through the landmark, but in a simplified way, as if it’s a stripe on a T-shirt. These simplifications of the land are hallmarks of Johnson’s work. “I found this one while driving through Monument Valley. It’s not the one of the Mittens or Totem or anything, but it’s still wonderful. The rock has this orangish-pink color in the soil. It almost permeates through to the atmosphere,” he says, adding that he painted in horses and a rider to show the scale of the mesa. “Edgar Payne did that a lot, adding little figures to show the scale. If you were to look real close you’d see they aren’t painted in much detail. They are just there to show how big the rest of the scene is.”

Other works include the cloudscape Dust and Spirit and Morning Shadows, Ranchos de Taos, which is an image of one of the most iconic churches in the Southwest, if not the world. “I’ve developed a real love for Taos. I really love the adobe and pueblos...I just adore it all. The church in Taos, though, it’s the most perfect building in the United States. It makes it hard to paint it because it’s been photographed millions of time from every angle,” he says. “But it has everything I love, including those big smooth organic forms.”

The church may have been photographed millions of times, and painted just as many times, but Johnson’s painting of the Ranchos de Taos church gets to the heart of why he admires Morandi: both artists are using the building blocks around them to tell different kinds of stories. Whether its bottles and vases or adobe and desert, the art is in the arrangement.

“I guess I feel like I have two opposing egos— one that loves the really vast sense of space and mass, and the other which is moved by simplicity and intimacy—the privacy of a personal world. I enjoy Morandi’s quiet, contemplative objects and the gentle dither of his brush in sort of the

opposite way I am drawn to Robert Motherwell’s monolithic shapes and dramatic tones,” Johnson says. “Eventually, I would really love to be able to combine those elements in the same painting. Sometimes I’m able to, but not often. I think the one I’m working on right now, of a pueblo and a mud oven, might be able to pull that off a little. We’ll see. A couple artists who I think were fantastic at doing so were Georgia O’Keeffe and Andrew Wyeth, and I’m a big fan of both of them as well. I have diverse interests in art, which doesn’t always make things easy.”

Combining the vast and the intimate is no small feat, but Johnson has figured it out in his own unique way.

Western Art Collector Previews Summer Small Works Exhibition

All in the Scale

This summer, Maxwell Alexander Gallery will mount a small works show featuring a number of its gallery artists. The show will have no particular theme, other than size, so the style and subject matter represented is far-reaching. Artists will include both contemporary and Western, and some who blur the gap. Among them are Teresa Elliot, Danny Galieote, David Grossmann, Matt Smith and Kim Wiggins. Over the past 30 years, much of Wiggin’s work has been focused on symbolism and his painting A Song in the Garden of Taos fits that bill. The work, which is part of his Voices Series, “centers on the isolated surroundings of Taos, New Mexico,” he explains. “By the end of the 19th century, American artists were searching desperately for a place and a subject that would set their work apart from the European school of art. The remote village of Taos soon emerged as the purest symbol of unblemished America…as if a fabled American Garden of Eden.

In Autumn Cottonwood and River View, Grossmann depicts one of his favorite cottonwoods. “It grows on the banks of the Colorado River in an open space that is filled with the sound of water and rustling leaves,” he says. “I especially love going there to paint this tree in the autumn when its leaves are radiant, caught in the breeze, and spreading the air with gold.”

Another landscape painting in the show is Smith’s Peralta Cliffs, which was inspired by an area the artist has painted and hiked for 35 year. “The day I set out to paint this piece, my goal was to focus on the cliffs,” says Smith. “Everything changed when I came across the dramatic, cast shadow on the arm of this lone saguaro. The cliffs were still present, but the plant ruled.”

Galieote has a love of old Hollywood cinema including vintage Westerns. It came about from his family having horses and a clothing store on Hollywood Boulevard in the 1940s through the 1960s. “Even though I wasn’t around to visit the store, I have my grandfather’s home movies. All the old film footage and his stories combined together to create this natural attraction and understanding of this era,” he shares. “I’ve always liked to glean stylistically from this period’s artistic design sensibilities as well as use them as my vessel to address timeless sociocultural themes in my work. In this case, my narrative revolves around this tough, independent cowgirl passing through for an afternoon libation.”

To view the work in the exhibition, click here.

American Art Collector Magazine Previews Summer Small Works Show

Size Matters

This July 13 to 27, Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles will present a small works group exhibition featuring artists working in both the contemporary and Western styles. Among those with works in the show are Kim Cogan, Danny Galieote, Michael Klein, Jeffrey T. Larson, Serge Marshennikov and Jacob A. Pfeiffer. The artist’s pieces measure smaller than 20 inches in size and are done in a variety of styles and subject matter to allow collectors and array of paintings to choose from.

Marshennikov’s 16-inch square piece Waves, features a woman lying atop folded fabric that is reminiscent of clothing items in Old Masters works. The artist explains, “I was inspired by the intriguing ‘Rembrandtesque’ collars of the 17th century whereas on a dish the given head was complemented expressiveness of the fabric represented ‘in a profile.”

Both Pfeiffer and Larson present still lifes with nontraditional imagery. Pfeiffer’s works are often tongue-in-cheek, while Larson’s pieces elevate unremarkable subjects to objects of beauty.

“I love incorporating visual puns and unusual juxtapositions in my work,” says Pfeiffer. “In my painting Bulbous, I am playing with pears and a light bulb. Both objects are similarly shaped and perfectly described by the title, and yet they are completely different.”

Larson’s painting A la carte depicts a whole fish in a takeout container. Explaining the inspiration behind the work, he says, “I live on the largest body of water (by surface area) in the world, Lake Superior. The herring is part of the bounty that this inland sea produces. On a practical level, the paper carton presents the smoked fish as a food offering the way we are accustomed to perceiving it. More importantly, I felt it created the perfect foil of whites to set of the beautiful metallic gold’s of the herring.”

To view works in the exhibition, click here.

Western Art Collector Magazine Previews John Moyer's Debut Exhibition

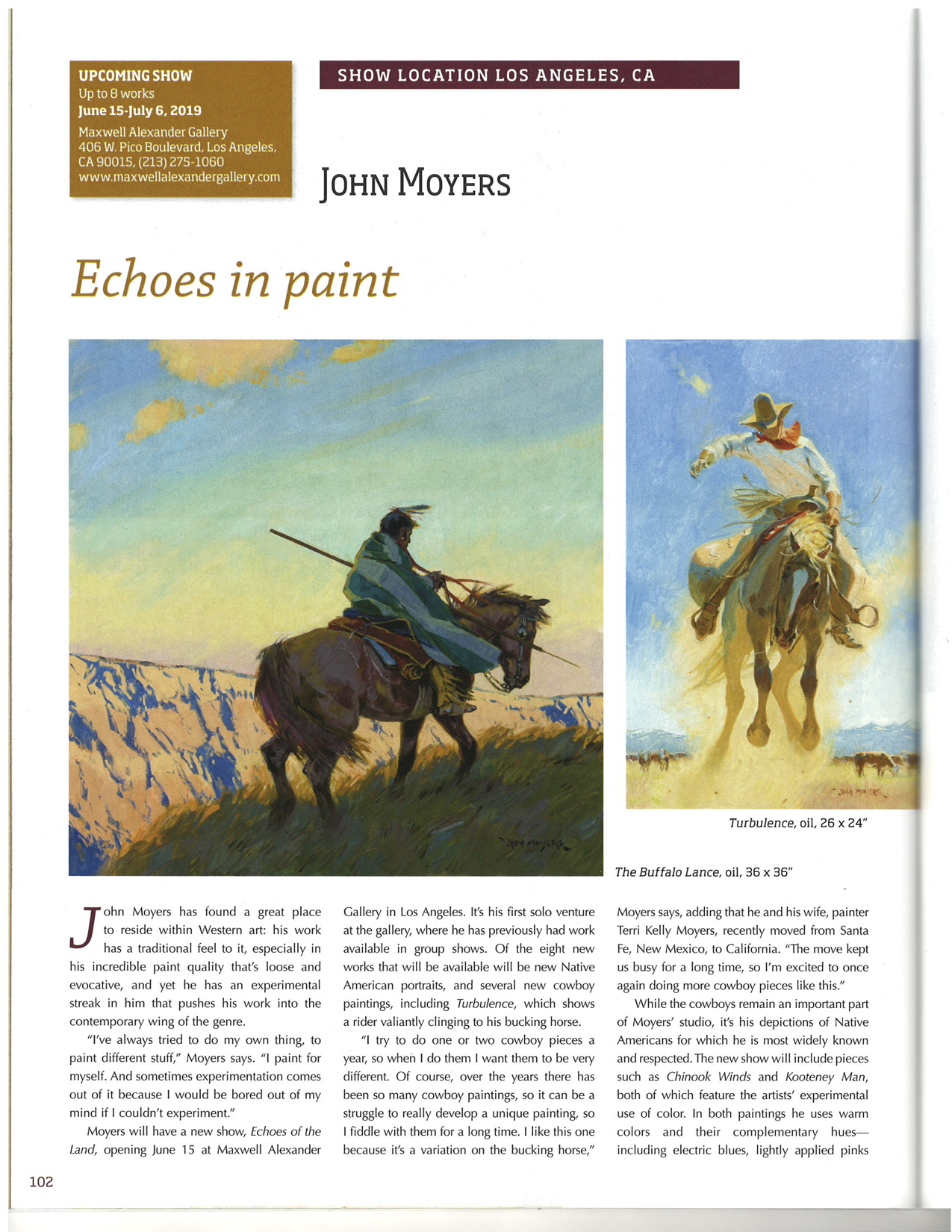

John Moyers has found a great place to reside within Western art: his work has a traditional feel to it, especially in his incredible paint quality that’s loose and evocative, and yet he has an experimental streak in him that pushes his work into the contemporary wing of the genre.

“I’ve always tried to do my own thing, to paint different stuff,” Moyers says. “I paint for myself. And sometimes experimentation comes out of it because I would be bored out of my mind if I couldn’t experiment.”

Moyers will have a new show, “Echoes of the Land,” opening June 15 at Maxwell alexander Gallery in Los Angeles. It’s his first solo venture at the gallery, where he has previously had work available in the group shows. Of the eight new works that will be available will be new Native American portraits, and several new cowboy paintings, including “Turbulence,” which shows a rider valiantly clinging to his bucking horse.

“I try to do one or two cowboy pieces a year, so when I do them I want them to be very different. Of course, over the years there has been so many cowboy paintings, so it can be a real struggle to really develop a unique painting, so I fiddle with them for a long time. I like this one because it’s a variation on the bucking horse,” Moyers says, adding that he and his wife, painter Terri Kelly Moyers, recently moved from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to California. “The move kept us busy for a long time, so I’m excited to once again be doing more cowboy pieces like this.”

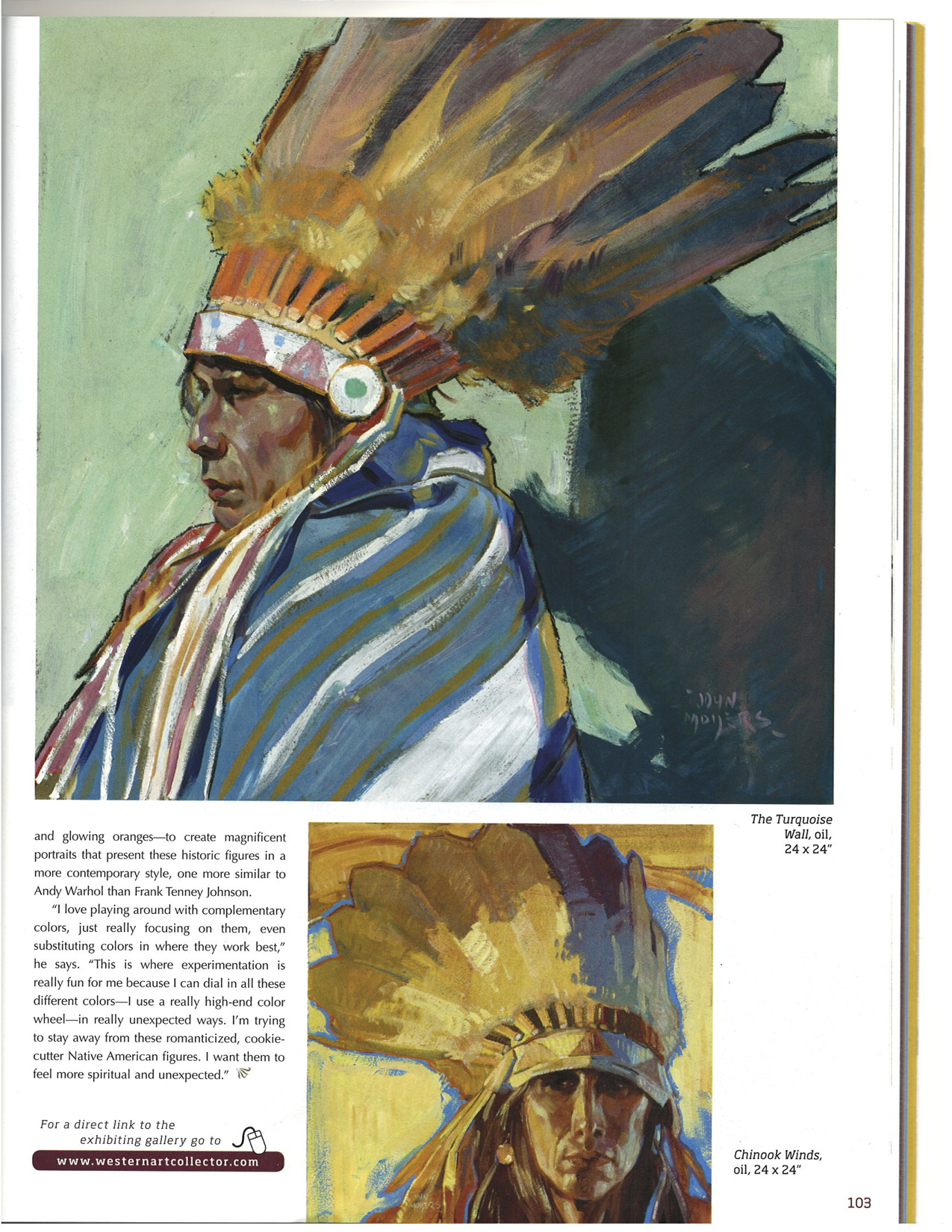

While the cowboys remain an important part of Moyers’ studio, it’s his depictions fo Native Americans for which he is most widely known and respected. The new show will include pieces suck as “Chinook Winds” and “Kooteney Man”, both of which feature the artist’s experimental use of color. In both paintings he’s uses warm colors and their complementary hues-including electric blues, lightly applied pinks, and glowing oranges- to create magnificent portraits that present these historic figures in a more contemporary style, one more similar to Andy Warhol than Frank Tenney Johnson.

“I love playing around with complementary colors, just really focusing on them, even substituting colors in where they work best,” he says. “This is where experimentation is really fun for me because I can dial in all these different colors – I use a really high-end color wheel- in really unexpected ways. I’m trying to stay away from these, romanticized, cookie-cutter Native American figures. I want them to feel more spiritual and unexpected.”

To view more work by John Moyers and the exhibition, click here.

Southwest Art Magazine Previews John Moyer's "Echoes of the Land"

In his first solo exhibition in over a decade, acclaimed painter John Moyers breathes new life into iconic western themes with his bright, modernist palette and invigorating, design-focused imagery. The show, which opens this month at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles, represents the next chapter in the artist’s ongoing efforts to “push his limits,” says gallery director Beau Alexander. “John is in his mid to late career, but he’s still developing his work; he isn’t creating the same old pieces,” observes Alexander. “He’s one of the best western artists alive, so for him to push the envelope is really exciting.”

Echoes of the Land, as the exhibition is titled, features some of the oil painter’s favorite motifs, including Southwestern landscapes and portraits of American Indians dressed in historically precise, trice-specific garments and headdresses from his own extensive artifact collection. To kick off the show, Moyers is on hand at an afternoon reception on Saturday, June 15, and he isn’t traveling far to attend: The longtime resident of Santa Fe, NM, moved to the Los Angeles area a few years ago. “It adds another artistic stamp to L.A.,” enthuses Alexander. “Many of today’s top western artist live within an hour of the city.’

Moyer’s move to the City of Angels has also enabled the pair to collaborate more closely. In preparation for this show, Alexander visited Moyers’ home near Pasadena. “When I walked into John’s studio and saw his painting of a bucking bronco, it caught me immediately,” says Alexander of the vivid, high-octane scene entitled “Turbulence”. “It almost feels like a William Herbert Dunton painting from the early 1900’s.”

Moyer’s, however, puts a contemporary spin on the classic western subject by portraying the rearing horse and his intrepid rider from a bold, head on view-point, rather than the more traditional side angle. “It creates a 3-D feeling-you feel the motion and the action in the painting,” notes Alexander.

Viewers can expect to see other refreshingly modern, convention-breaking perspectives like this in the show. “I’m having fun,” says Moyers. “I’m experimenting with color and design a lot. As an artist, you always have to try new things.” –Kim Agricola

To view the exhibition, click here.

Susan Lyon “Gems” 24” x 18” Oil

Susan Lyon wins top prize at Oil Painters of America

Maxwell Alexander Gallery is pleased to announce that artist Susan Lyon won the Gold Medal Award in the Associate and Signature Division at the 28th National Exhibition of Oil Painters of America. Showcased at the Illume Gallery of Fine Art, Lyon’s piece “Gems” received the top prize of $25,000. Oil Painters of America features premier realism artists, and Lyon’s win is a credit to her skill and dedication. To inquire about available works by Susan Lyon, please contact Maxwell Alexander Gallery for details.

Western Art Collector Magazine Previews the Bowman Solo Exhibition in a Six Page Write Up:

Layers of Light

Eric Bowman brings drama to the light and shadow of the IWest in a new show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery.

By Michael Clawson

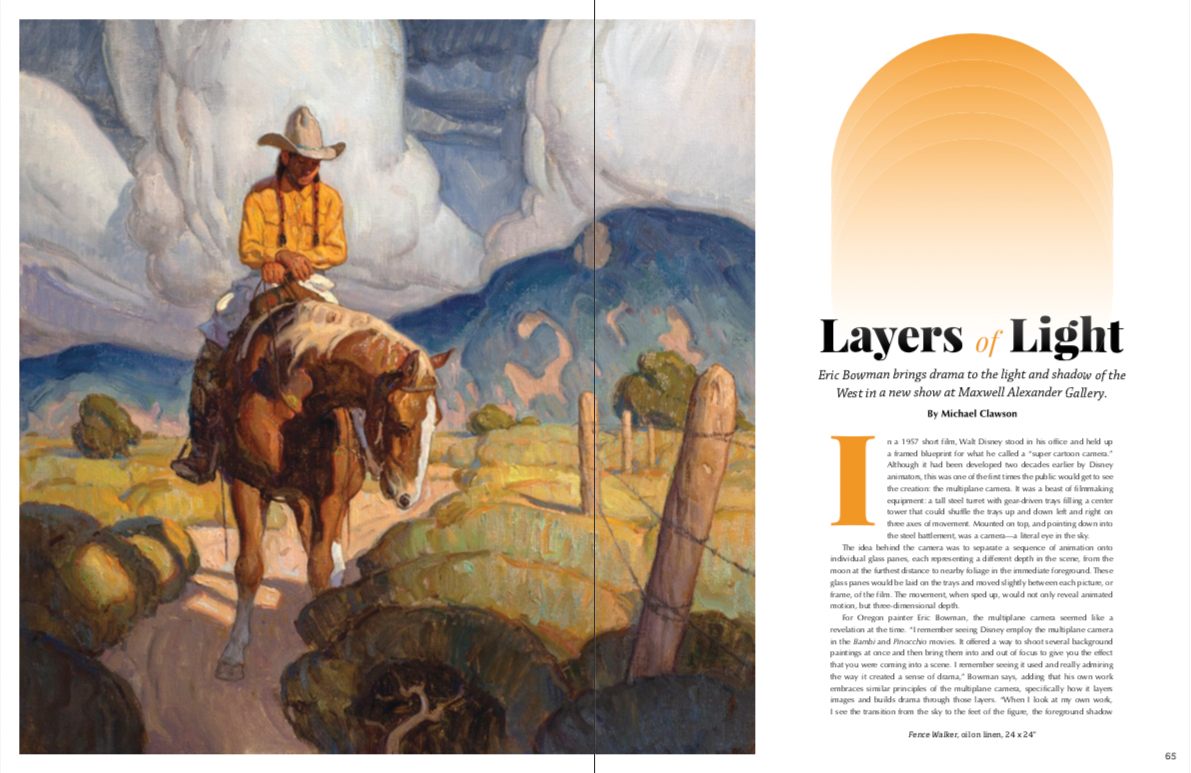

In a 1957 short film, Walt Disney stood in his office and held up a framed blueprint for what he called a “super cartoon camera.” Although it had been developed two decades earlier by Disney animators, this was one of the first times the public would get to see the creation: the multiplane camera. It was a beast of filmmaking equipment: a tall steel turret with gear-driven trays filling a center tower that could shuffle the trays up and down left and right on three axes of movement. Mounted on top, and pointing down into the steel battlement, was a camera—a literal eye in the sky.

The idea behind the camera was to separate a sequence of animation onto individual glass panes, each representing a different depth in the scene, from the moon at the furthest distance to nearby foliage in the immediate foreground. These glass panes would be laid on the trays and moved slightly between each picture, or frame, of the film. The movement, when sped up, would not only reveal animated motion, but three-dimensional depth.

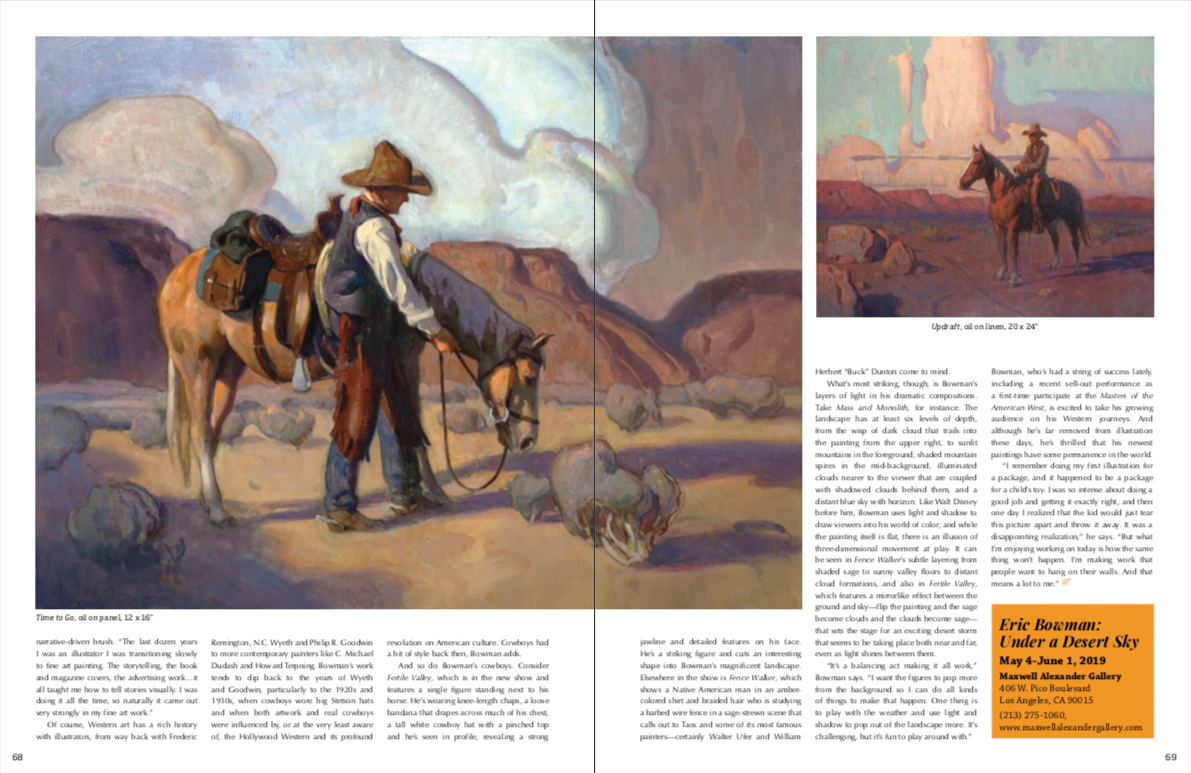

For Oregon painter Eric Bowman, the multiplane camera seemed like a revelation at the time. “I remember seeing Disney employ the multiplane camera in the Bambi and Pinocchio movies. It offered a way to shoot several background paintings at once and then bring them into and out of focus to give you the effect that you were coming into a scene. I remember seeing it used and really admiring the way it created a sense of drama,” Bowman says, adding that his own work embraces similar principles of the multiplane camera, specifically how it layers images and builds drama through those layers. “When I look at my own work, I see the transition from the sky to the feet of the figure, the foreground shadow versus the background shadow, the way the lighting shifts and illuminates one cloud but then obscures another...creating these layers of light is a vehicle, a mechanism to create more interest in my paintings.”

Those layers, and the stories they help tell, will be the stars of Bowman’s new show, Under a Desert Sky, opening May 4 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles. The show will feature a dozen new cowboy works from the painter, who uses his paintings to introduce story ideas that a viewer can then ride away with in any direction. “I just love continuing the open- ended dialogue about the cowboy. I paint cowboys who are sort of out of their elements, but also these heroic and iconic figures that have been portrayed in history,” he says. “I like to start a narrative for the viewer and then give them enough space to pick it up and finish it. This particular show might have a bit more of a cohesive feel to it—there is a continuity factor in that they are all set in the desert and there are cloudy skies that make up a lot of the design—but it’s still up to the viewer to determine what happens next.”

His storytelling chops came from a familiar place in the Western world: illustration. Bowman worked as a professional illustrator for 30 years starting in 1983. “I was doing a little bit of everything. All traditional, no digital work. I started out learning a bunch of different mediums and ended up sort of being a jack of all trades before I really settled into oil painting. But I did it all, everything from billboards to postage stamps, and covers for Time, Saturday Evening Post, Boy’s Life, Field & Stream...it might be easier to give you a list of who I didn’t do work for,” Bowman says, adding he never did National Geographic because its adherence to historically accurate detail didn’t suit his looser, more narrative-driven brush. “The last dozen years I was an illustrator I was transitioning slowly to fine art painting. The storytelling, the book and magazine covers, the advertising work...it all taught me how to tell stories visually. I was doing it all the time, so naturally it came out very strongly in my fine art work.”

Of course, Western art has a rich history with illustrators, from way back with Frederic Remington, N.C. Wyeth and Philip R. Goodwin to more contemporary painters like C. Michael Dudash and Howard Terpning. Bowman’s work tends to dip back to the years of Wyeth and Goodwin, particularly to the 1920s and 1930s, when cowboys wore big Stetson hats and when both artwork and real cowboys were influenced by, or at the very least aware of, the Hollywood Western and its profound revolution on American culture. Cowboys had a bit of style back then, Bowman adds.

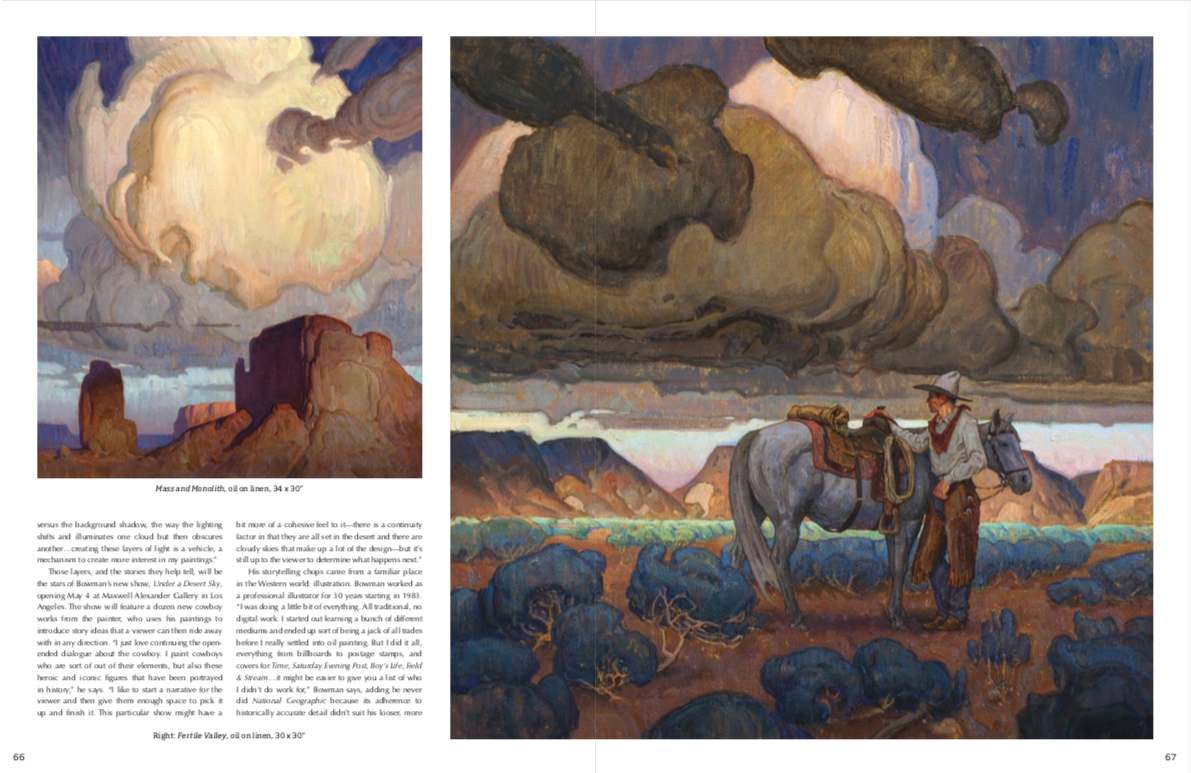

And so do Bowman’s cowboys. Consider Fertile Valley, which is in the new show and features a single figure standing next to his horse. He’s wearing knee-length chaps, a loose bandana that drapes across much of his chest, a tall white cowboy hat with a pinched top and he’s seen in profile, revealing a strong Herbert “Buck” Dunton come to mind.

What’s most striking, though, is Bowman’s layers of light in his dramatic compositions. Take Mass and Monolith, for instance. The landscape has at least six levels of depth, from the wisp of dark cloud that trails into the painting from the upper right, to sunlit mountains in the foreground, shaded mountain spires in the mid-background, illuminated clouds nearer to the viewer that are coupled with shadowed clouds behind them, and a distant blue sky with horizon. Like Walt Disney before him, Bowman uses light and shadow to draw viewers into his world of color; and while the painting itself is flat, there is an illusion of three-dimensional movement at play. It can be seen in Fence Walker’s subtle layering from shaded sage to sunny valley floors to distant cloud formations, and also in Fertile Valley, which features a mirrorlike effect between the ground and sky—flip the painting and the sage become clouds and the clouds become sage— that sets the stage for an exciting desert storm that seems to be taking place both near and far, even as light shines between them.

“It’s a balancing act making it all work,” Bowman says. “I want the figures to pop more from the background so I can do all kinds of things to make that happen. One thing is to play with the weather and use light and shadow to pop out of the landscape more. It’s challenging, but it’s fun to play around with.”

Bowman, who’s had a string of success lately, including a recent sell-out performance as a first-time participate at the Masters of the American West, is excited to take his growing audience on his Western journeys. And although he’s far removed from illustration these days, he’s thrilled that his newest paintings have some permanence in the world.

“I remember doing my first illustration for a package, and it happened to be a package for a child’s toy. I was so intense about doing a good job and getting it exactly right, and then one day I realized that the kid would just tear this picture apart and throw it away. It was a disappointing realization,” he says. “But what I’m enjoying working on today is how the same thing won’t happen. I’m making work that people want to hang on their walls. And that means a lot to me.”

ARTICLE FEATURED IN WESTERN ART COLLECTION MAGAZINE APRIL 2019

THE TIA COLLECTION ACQUIRES A MAJOR WORK BY LOGAN MAXWELL HAGEGE

One of the most important Western art collections in the world, the Santa Fe-based Tia Collection, has recently acquired Logan Maxwell Hagege’s massive new painting Taos Plains. The 60-inch-by-40-inch painting, depicting a single figure on horseback and framed against a billowing cloud on the horizon, will join works by some of the most important painters of the West, including artists who spent a great deal of time in New Mexico, such as Alexandre Hogue, Cady Wells, Victor Higgins, Walter Ufer, Stuart Davis and many others.

The collection is privately owned, though portions of it are frequently traveling around the country to loaned exhibitions that expose the works to countless new museumgoers. Currently there is a major Tia Collection show, New Beginnings: An American Story of Romantics and Modernists in the West, ongoing now at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West in Scottsdale, Arizona. It runs through September 22.

Taos Plains is the second Hagege work in the Tia Collection, which leans toward modernism. “Tia Collection has been avidly following Logan’s career since its first acquisition of his work in 2009/2010 of Taos Profile, currently on loan to the Booth Western Art Museum in Georgia,” says Laura Finlay Smith, Tia curator. “We were excited to add Taos Plains to the collection in 2018 as a way to continue not only supporting him as an artist, but also to create a conversation between the two works, demonstrating the development of his well-known painting style over almost a decade.”

Hagege, who’s still under 40 years old, has a growing list of museums and important collections that have acquired his work including the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis and the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles.

WESTERN ART COLLECTOR PREVIEWS GRANT REDDEN'S "VIEWS FROM THE RANCH"

Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles will present new works from Cowboy Artists of America member Grant Redden beginning April 6. Redden, who frequently explores less-traveled areas of the West such as sheepherding and farming, will focus entirely on classic cowboy material for this new show, his first solo exhibition at the gallery.

“These will be signature paintings, paintings with subject matter that is very familiar to me,” he says. “I’ll also be informed by historical painters for these works. I’m never consciously trying to make my work like theirs, but they certainly inspire me, especially when I’m going through depression and doubt—something all painters feel at some point in the studio—with every brushstroke. That may sound like it’s miserable to be an artist, but it’s not. It’s actually a lot of fun, but artists doubt everything they do sometimes. It’s part of the process.”

Redden will be turning much of his attention to cowboys from the early 1900s, particularly the 1920s and 1930s. William Herbert “Buck” Dunton and Frank Tenney Johnson are two artists who speak to the time period he’s painting. In one new painting, The Call of the Night Bird, Redden seems to call out

to Johnson with a nocturne scene. But where Johnson would use looser brushstrokes and more primal paint application, Redden paints a tighter picture with more detail and more nuance in the light. It creates a wonderful call- and-response aspect with Johnson, one of the great cowboy painters.

The Wyoming artist says that he did not use a photo reference for the painting, simply because it’s nearly impossible to capture moonlight in a photograph or even a sketch. “Paintings like this are almost entirely from imagination, because once you’re out there in the moonlight there is not much information

to record. You have to invent and imagine it all in the studio,” he says. “It’s kind of a theatrical production with the nocturne. Some are successful, and some aren’t. But when they’re successful it’s a reward because it’s all you, every piece of it.”

In the piece the horse is white, mostly because white horses are more fascinating for the artist and the viewer. “A white horse has so much reflection that it can make things around it more interesting. They’re like aspen trees in that way,” he adds. “As for black horses, just hit me in the back of the head. They just absorb all the light around them. If you can successfully paint a black horse you deserve a medal.”

Another work in the show is Old Unreliable, a painting of the timeless image of a rider on a bucking horse. The painting has a pleasing convergence of lines—from distant mountain ridges and rocky cliff faces to closer outcroppings carved into the desert soil—that guide the eye toward the leaping horse and its cool, collected rider who clings to its back.

Redden’s first solo show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery will continue through April 27. VIEW IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION HERE

Southwest Art Magazine on Grant Redden's Upcoming Solo Show

In a small solo show opening at Maxwell Alexander Gallery on Saturday, April 6, Wyoming artist Grand Redden captures timeless vignettes of the cowboy, his horse, and the land upon which he works. If the showcase conjures the spirit of early cowboy artists like Fran Tenney Johnson and W. Herbert Dunton, who captured the Old West, Redden wouldn’t mind the comparison. In the half dozen oil paintings he brings to the show, the artist seeks to share a bit of his own western heritage with viewers.

Redden’s paternal ancestors were among the first pioneers to settle in southwest Wyoming, and he himself grew up in the region on his father’s sheep and cattle ranch. Today he lives with his wife and family in the area, where he raises a small herd of sheep, chickens, and a few cows on 120 acres of pastureland. It’s a way of life that has always appealed to the artist— modernized methods of farming aside. “I really don’t have much interest in painting tractors,” he admits unapologetically. “With some of my work, I try to make it look like the cowboy and western life from 1900 to the 1930s. The Zane Grey and Gene Autry period is an exciting and interesting time to people, and I think contemporary desires are reaching back to that time.”

Over the nearly three decades he has been painting, Redden has studied with acclaimed artists ranging from Jim Norton to Gerald Fritzler to Walt Gonske. He has also closely observed the techniques of a variety of living and deceased masters. “How I paint is as important to me as what I paint,” says Redden. who was inducted into the exclusive Cowboy Artists of America in 2012. “The longer I paint, the more excited I get about the craftsmanship that goes into a well-made painting—the textures, the colors, the design. I’m more focused on using large shapes and bright colors in a harmonious way, and I use a lot of sanding and glazing.”

Also propelling Redden forward on his creative path is the ongoing urge to share his world with others. “If you haven’t ridden a bobsled with a load of hay, it’s amazing—the sounds, the smells,” says the artist. Of course, while he can’t arrange for viewers to physically experience such pleasures he adds, “I can paint it for them.” And being able to do that, says Redden, “is like being paid to eat ice cream.”

WESTERN ART COLLECTOR MAGAZINE TAKES A LOOK AT THE FORTHCOMING "OUT WEST" EXHIBITION

Three Perspectives

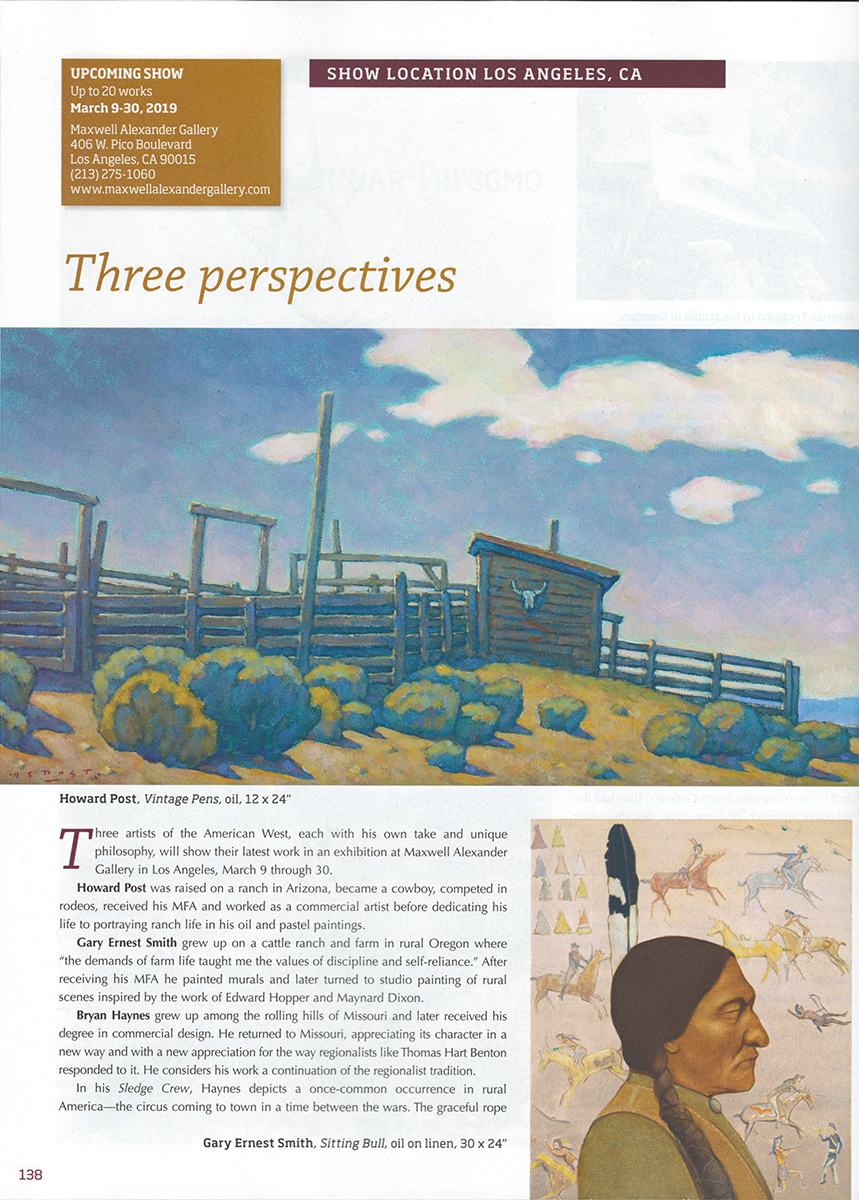

Three artists of the American West, each with his own take and unique philosophy, will show their latest work in an exhibition at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles, March 9 through 30.

Howard Post was raised on a ranch in Arizona, became a cowboy, competed in rodeos, received his MFA and worked as a commercial artist before dedicating his life to portraying ranch life in his oil and pastel paintings.

Gary Ernest Smith grew up on a cattle ranch and farm in rural Oregon where “the demands of farm life taught me the values of discipline and self-reliance.” After receiving his MFA he painted murals and later turned to studio painting of rural scenes inspired by the work of Edward Hopper and Maynard Dixon.

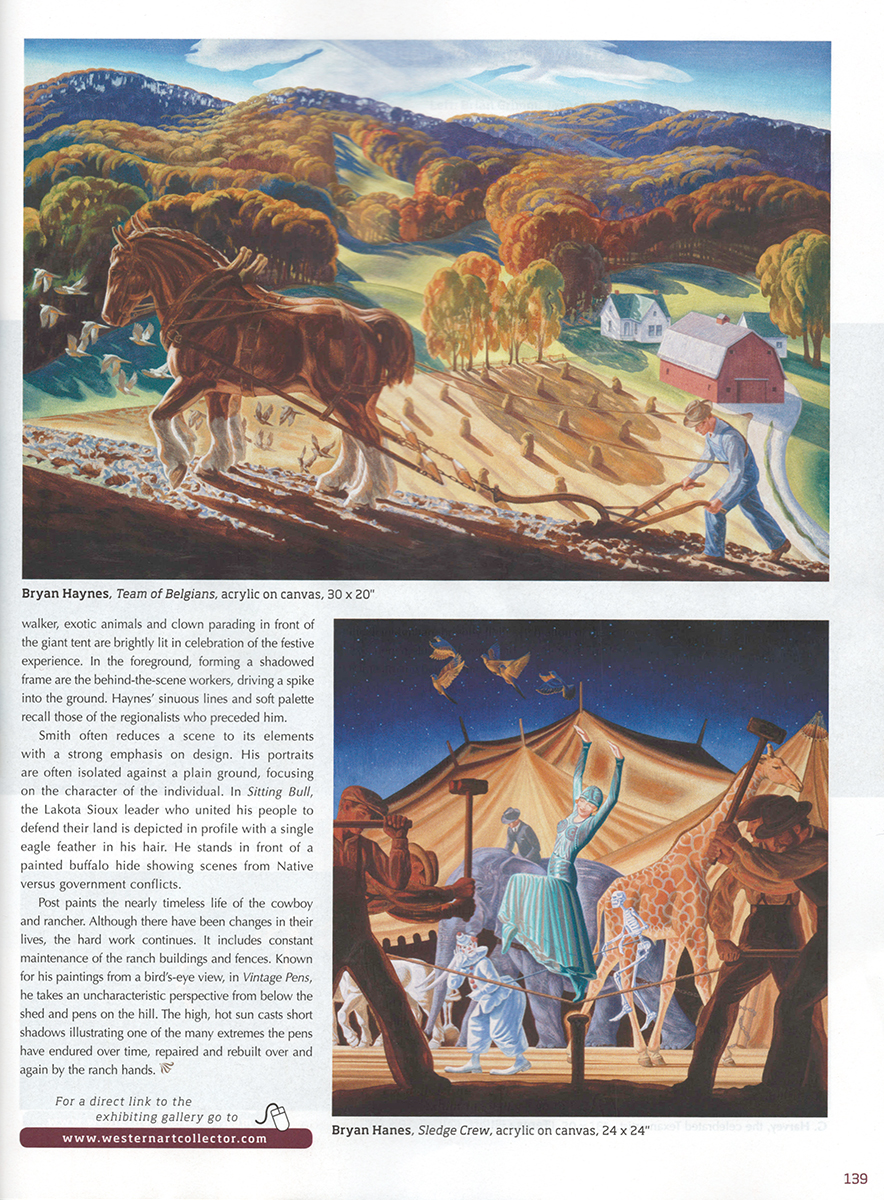

Bryan Haynes grew up among the rolling hills of Missouri and later received his degree in commercial design. He returned to Missouri, appreciating its character in a new way and with a new appreciation for the way regionalists like Thomas hart Benton responded to it. He considers his work a continuation of the regionalist tradition.

In his Sledge Crew, Haynes depicts a once-common occurrence in rural America— the circus coming to town in a time between the wars. The graceful rope walker, exotic animals and clown parading in front of the giant tent are brightly lit in celebration of the festive experience. In the foreground, forming a shadowed frame are the behind-the-scenes workers, driving a spoke into the ground. Haynes’ sinuous line and soft palette recall those of the regionalists who preceded him.

Smith often reduces a scene to its elements with a strong emphasis on design. His portraits are often isolated against a plain ground, focusing on the character of the individual. In Sitting Bull, the Lakota Sioux leader who united his people to defend their land is depicted in profile with a single eagle feather in his hair. He stands in front of a painted buffalo hide showing scenes from Native versus government conflicts.

Post paints the nearly timeless life of the cowboy and rancher. Although there have been changes in their lives, the hard work continues. It includes constant maintenance of the ranch buildings and fences. Known for his paintings from a bird’s-eye view, in Vintage Pens, he takes an uncharacteristic perspective from below the shed and pens on the hill. The high, hot sun casts short shadows illustrating one of the many extremes the pens have endured over time, repaired and rebuilt over and again by the ranch hands.

Desert Survey Book by Logan Maxwell Hagege

Desert Survey, the new book, showcasing over 150 pages of Logan Maxwell Hagege’s most iconic works. Releasing February 24, 2019 at 10am PT. The first printing of Desert Survey is limited to 500 signed and numbered books.

Available to purchase exclusively at MaxwellAlexanderGallery.com/shop/

Western Art Collector Magazine Highlights Maxwell Alexander Gallery

Maxwell Alexander Gallery is located in the South Park district of downtown Los Angeles, just a couple streets over from the Convention Center and Staples Center. In recent years, downtown LA has become one of the most sought after locations in Los Angeles. Maxwell Alexander Gallery is continuing its service to out-of-state clientele but has also gained a group of new collectors this past year who are new residents of downtown LA. As a result, sales have doubled in 2018 and the gallery looks forward to continue the trend in 2019. Keeping things interesting with multiple exhibitions running each month in its front and south galleries, the gallery’s primary focus is on high-quality art. “I can say with confidence, no other gallery in the Southwestern market has a roster as strong as ours. We are developing new artists’ careers, but we are lucky to have the biggest names all under on roof,” says Beau Alexander, president. In March, Maxwell Alexander Gallery is hosting a three-person exhibition featuring legendary painters Howard Post, Gary Ernest-Smith and Bryan Haynes. In April, an exhibition will be held for Grant Redden, his Los Angeles debut. In May the gallery hosts the thirst consecutive solo exhibition for Eric Bowman.

American Art Collector Magazine Interviews Beau Alexander about Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Downtown Los Angeles

Maxwell Alexander Gallery is a leading West Coast destination for some of the country’s best realists, dubbed “The New Breed of Fine Art.” The gallery specializes in middle and early career artists with exceptional technique and a unique vision. Noted artists include Jeremy Mann, Serge Marshennikov, Cesar Santos, Joseph Todorovitch, Kim Cogan, Michael Klein, Joshua LaRock and David Kassan.

“Maxwell Alexander Gallery is located in the South Park district of downtown Los Angeles, just a couple streets over from the Convention Center and Staples Center. In recent years, downtown LA has become one of the most sought-after locations in Los Angeles. Recent articles have shown 35 new high-rise building projects, many of them including residential units,” says Beau Alexander, president of the gallery.

“Needless to say, the market is booming. We are continuing to service our out-of-state clientele, but we’ve also gained a whole group of new clients this past year who are new residents of downtown LA. As a result, sales have doubled in 2018 and we look forward to continue the trend in 2019.

He continues, “The roster of master artists exhibited in our white walled, 16-foot high ceiling contemporary gallery, has transformed typically modern collectors to take a second look at contemporary realism— and add works to their growing collections. We are thrilled to be in the middle of this growing market and a worldwide destination for enthusiastic collectors.”

In February, the gallery will host an exhibition for Todorovitch featuring his new series of muted-toned figurative works that feature hist of color, creating a dreamlike sensation.

American Art Collector Magazine's Upcoming Show Preview on Joseph Todorovitch

Low Chroma

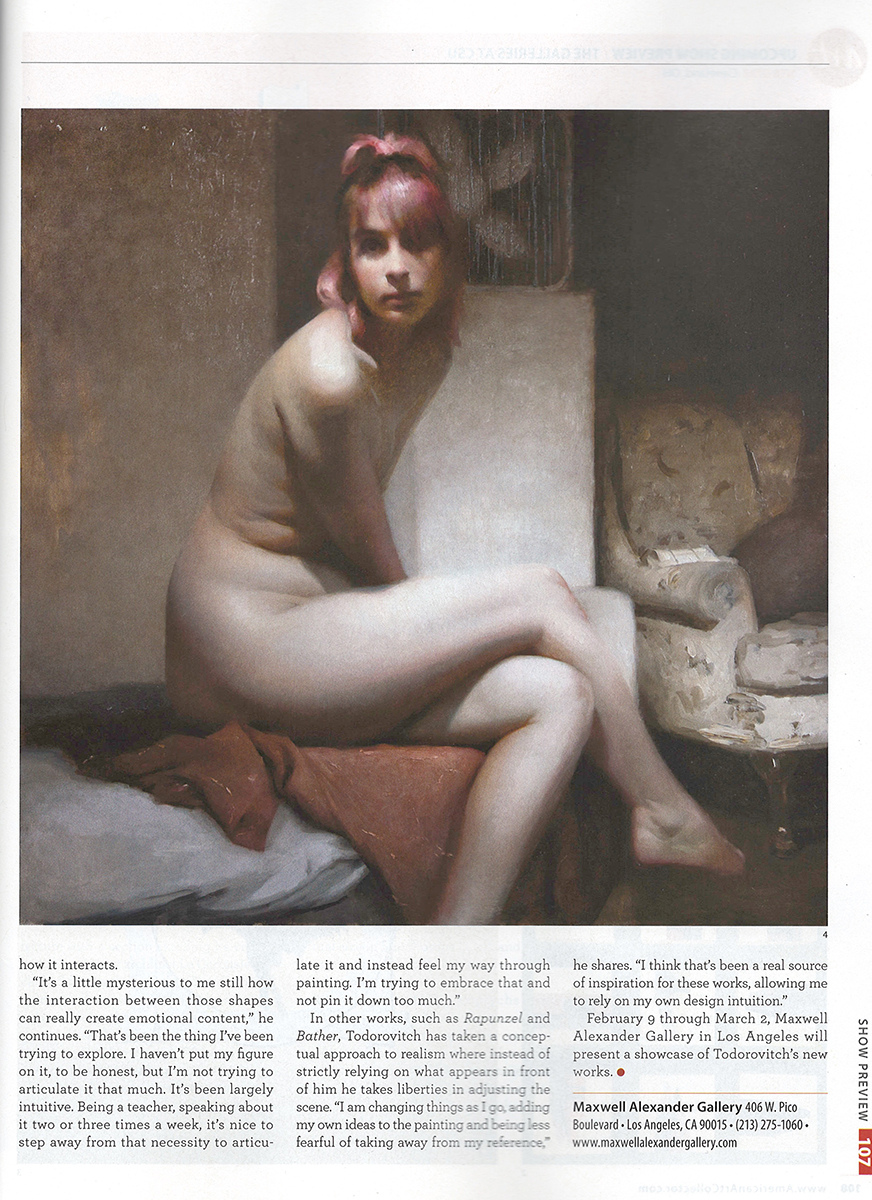

As an artist and instructor, Joseph Todorovitch is always exploring new methods of how to apply paint to a canvas— whether that is changing up the tools he uses or experimenting with a new color palette. This penchant to push the boundaries artistically helps keep Todorovitch’s figurative paintings fresh and moving into new series. Most recently, he has been aiming for simplicity in his paintings by limiting the tools he uses and working in a relatively low chroma color palette.

“Even though the color is relatively neutral, I do find there is more and more subtlety, which is nice,” says the California-based artist. “There’s quite a bit of color. It feels poetic to me as opposed to some of my earlier work a year or two ago that was really high chroma.”

Another important element to this latest body of work is that the paintings seem to have more feeling to them, such as in the work Wonder where a woman stops to pluck a flower from a blooming field below. “For some reason, simplifying has really been a good, direct path to creating more feeling in the painting. That’s been a fun discovery,” Todorovitch explains. “[Wonder] is the two-value statement, a dark figure against a light background, and a very simple compositional device to create a compositional balance. It’s a notan— the physical design of simple light and dark and how it interacts.

“It’s a little mysterious to me still how the interaction between those shapes can really create emotional content,” he continues. “That’s been the thing I’ve been trying to explore. I haven’t put my finger on it, to be honest, but I’m not trying to articulate it that much. It’s been largely intuitive. Being a teacher, speaking about it two or three times a week, it’s nice to step away from that necessity to articulate it and instead feel my way through painting. I’m trying to embrace that and not pin it down too much.”

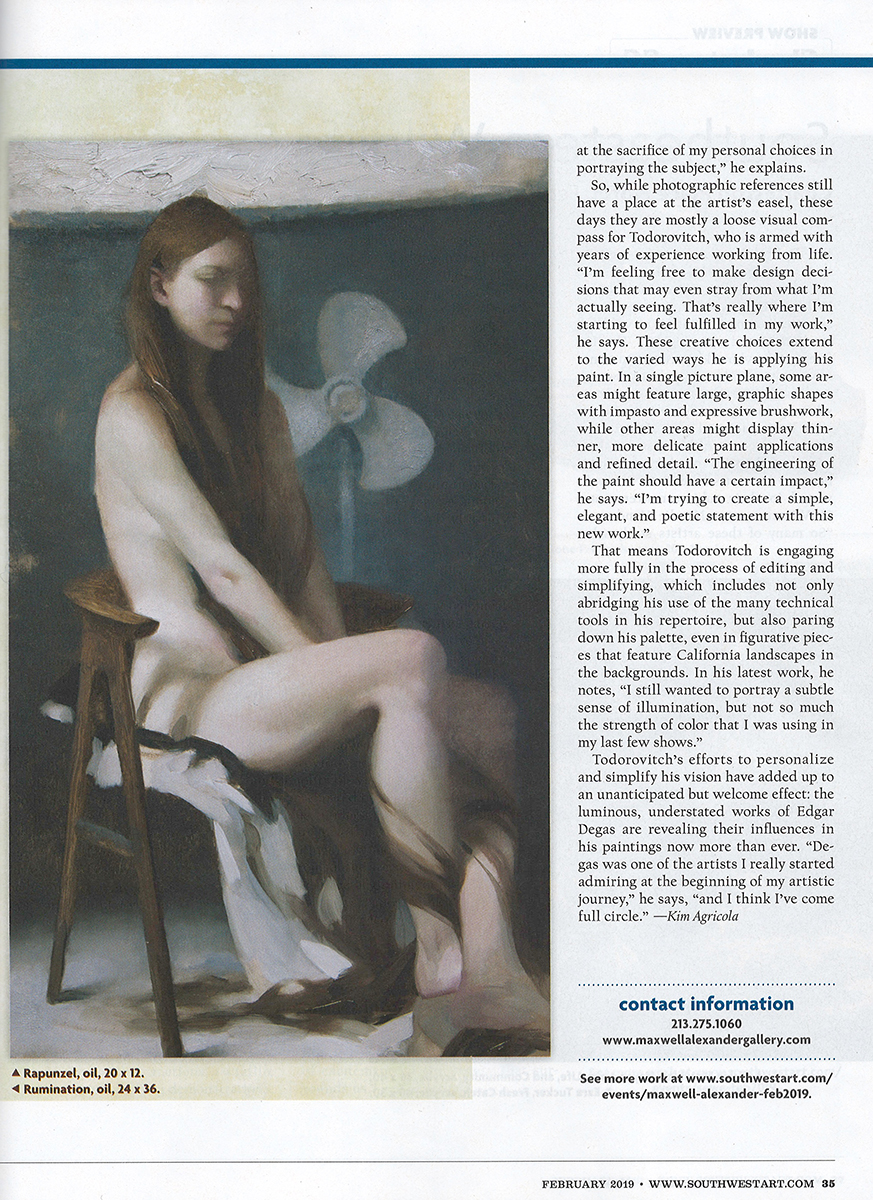

In other works, such as Rapunzel and Bather, Todorovitch has taken a conceptual approach to realism where instead of strictly relying on what appears in front of him he takes liberties in adjusting the scene. “I am changing things as I go, adding my own ideas to the painting and being less fearful of taking away from my reference,” he shares. “I think that’s been a real source of inspiration for these works, allowing me to rely on my own design intuition.”

February 9 through March 2, Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles will present a showcase of Todorovitch’s new works.

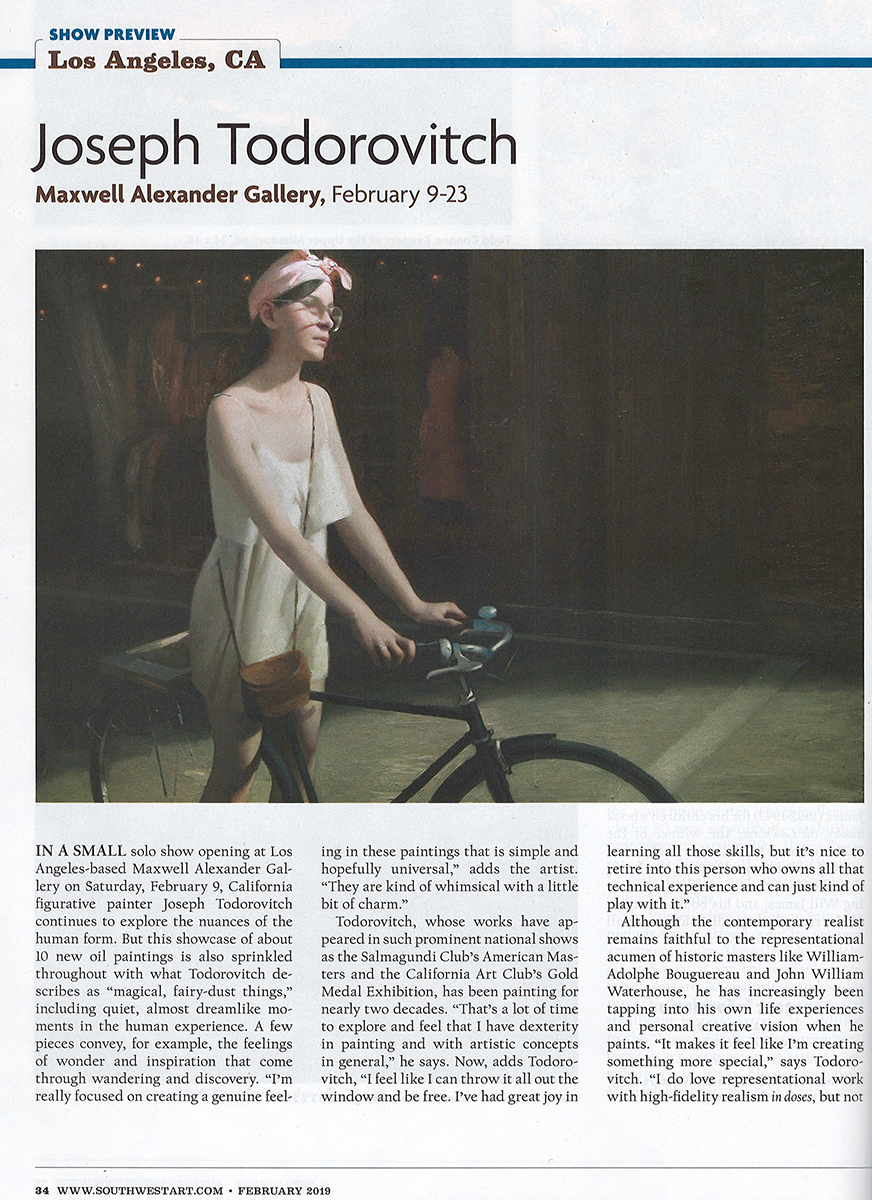

Southwest Art Magazine Previews Joseph Todorovitch's Upcoming Solo Show

In a small solo show opening at Los Angeles-based Maxwell Alexander Gallery on Saturday, February 9, California figurative painter Joseph Todorovitch continues to explore the nuances of the human form. But this showcase of about 10 new oil paintings is also sprinkled throughout with what Todorovitch describes as “magical, fairy-dust things,” including quiet, almost dreamlike moments in the human experience. A few pieces convey, for example, the feelings of wonder and inspiration that come through wandering and discovery. “I’m really focused on creating a genuine feeling in these paintings that is simple and hopefully universal,” adds the artist. “They are kind of whimsical with a little bit of charm.”

Todorovitch, whose works have appeared in such prominent national shows as the Salmagundi Club’s American Masters and the California Art Club’s Gold Medal Exhibition, has been painting for nearly two decades. “That’s a lot of time to explore and feel that I have dexterity in painting and with artistic concepts in general,” he says. Now, adds Todorovitch, “I feel like I can throw it all out the window and be free. I’ve had great joy in learning all those skills, but it’s nice to retire into this person who owns all the technical experience and can just kind of play with it.”

Although the contemporary realism remains faithful to the representational acumen of historic masters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and John William Waterhouse, he has increasingly been tapping into his own life experiences and personal creative vision when he paints. “It makes it feel like I’m creating something more special,” says Todorovitch. “I do love representational work with high-fidelity realism in doses, but not at the sacrifice of my personal choices in portraying the subject,” he explains.

So, while photographic references still have a place at the artist’s easel, these days they are mostly a loose visual compass for Todorovitch, who is armed with years of experience working from life. “I’m feeling free to make design decisions that may even stray from what I’m actually seeing. That’s really where I’m starting to feel fulfilled in my work,” he says. These creative choices extend to the varied ways he is applying his paint. In a single picture plane, some areas might feature large, graphic shapes with impasto and expressive brushwork, while other areas might display thinner, more delicate paint applications and refined detail. “The engineering of the paint should have a certain impact,” he says. “I’m trying to create a simple, elegant and poetic statement with this new work.”

That means Todorovitch is engaging more fully in the process of editing and simplifying, which includes not only abridging his use of the many technical tools in his repertoire, but also paring down his palette, even in figurative pieces that feature California landscapes in the backgrounds. In his latest work, he notes, “I still wanted to portray a subtle sense of illumination, but not so much the strength of color that I was using in my last few shows.”

Todorovitch’s efforts to personalize and simplify his vision have added up to an unanticipated but welcome effect: the luminous, understated works of Edgar Degas are revealing their influences in his paintings now more than ever. “Degas was one of the artists I really started admiring at the beginning of my artistic journey,” he says, “and I think I’ve come full circle.” — Kim Agricola

Western Art & Architecture Magazine Highlights Teresa Elliot's Work

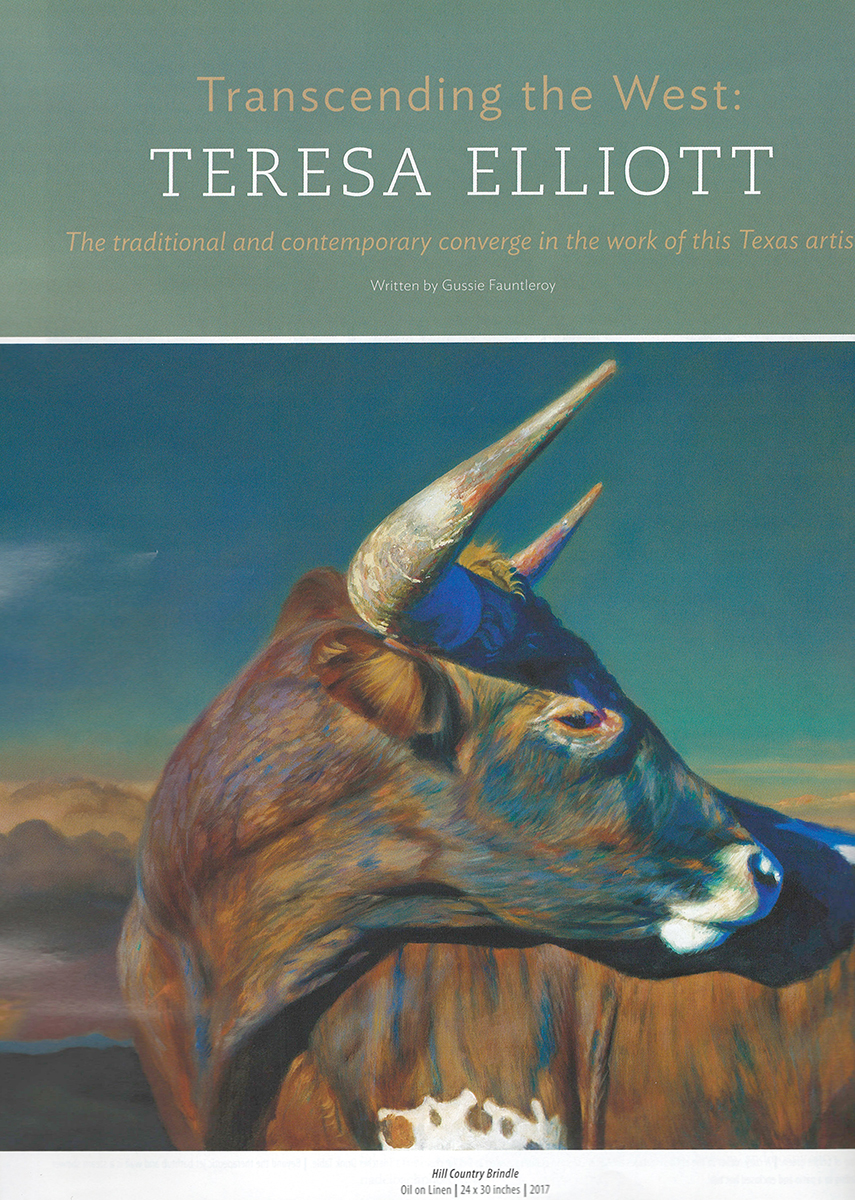

Transcending the West: Teresa Elliott

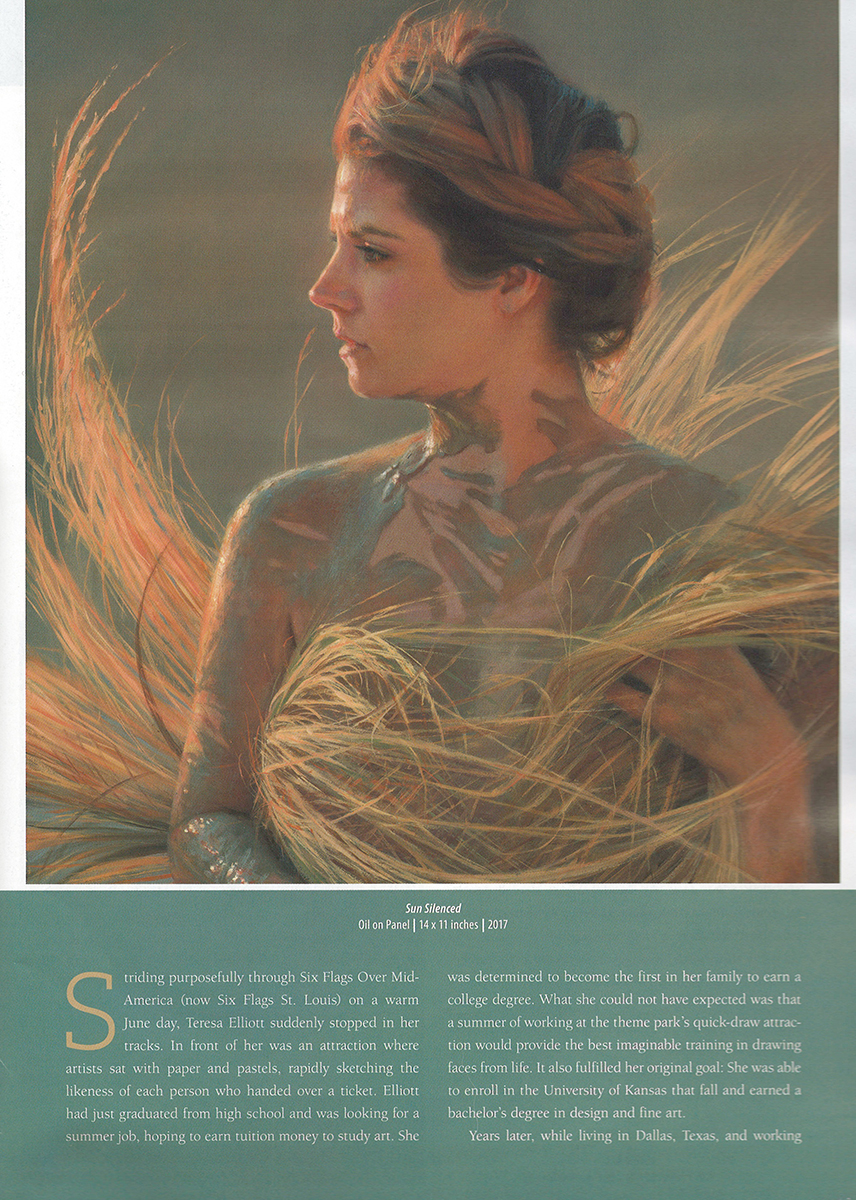

Striding purposefully through Six Flags Over Mid-America (now Six Flags St. Louis) on a warm June day. Teresa Elliott suddenly stopped in her tracks. In front of her was an attraction where artists sat with paper and pastels, rapidly sketching the likeness of each person who handed over a ticket. Elliott had just graduated from high school and was looking for a summer job, hoping to earn tuition money to study art. She was determined to become the first in her family to earn a college degree. What she could not have expected was that a summer of working at the theme park’s quick-draw attraction would provide the best imaginable training in drawing faces from life. It also fulfilled her original goal: She was able to enroll in the University of Kansas that fall and earned a bachelor’s degree in design and fine art.

Years later, while living in Dallas, Texas and working as a freelance fashion illustrator, Elliott had another pivotal chance encounter. As she drove past a small pasture in suburban Fort Worth, she was struck by the beauty of a small group of longhorn cattle grazing there — the graceful curves of their horns, their gentle faces, the rich colors of their coats. She returned with her sketchpad and camera in the sunset’s warm glow, and later, she painted her first longhorn. Considering it simply for her own pleasure, Elliott never intended to sell it.

Fortunately, life had other plans. Within a few years, she received the first of many awards for her longhorn paintings, and her work began to gain recognition in and beyond the world of traditional Western art. Among her honors over the years: Grand Prize from the America China Oil Painting Artists League, People’s Choice at the Coor’s Western Art Exhibit & Sale, and , most recently, the Chairman’s Choice Award (for the third time) at the 2018 Art Renewal Center’s International Salon.

“Teresa is a fabulously skilled realist painter and an unmistakably Texas artist,” says Joseph M. Bravo, a Texas-based art critic, curator and former museum director. “Yet, she’s clearly contemporary in her optic. There’s something transcendent about her work that exceeds the Southwest.”

Indeed, Elliott’s art has garnered national and international acclaim and a rapidly growing collector base. In March, she takes part in the annual Night of Artists show at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, where her work has always sold out. And then in October, Elliott and painter Jill Soukup will share a two-artist show at Gallery 1261 in Denver, Colorado.

The world of galleries and art museums was not even on Elliott’s radar when she was growing up. As the daughter of a salesman whose work took the family to St. Louis, Kansas City, and Oklahoma City, she loved to draw but had little exposure to original art. Then, in elementary school, her parents bought a children’s encyclopedia set with a special volume on art. Sitting for hours with the big book open on her lap, she soaked up the pictures to the point that many remain imprinted in her mind today.

After her summer of intensive informal training as part of the amusement park’s quick-draw team, Elliott focused primarily on figurative art. Her skills were so remarkable that her college art professors recommended her when detectives came seeking an artist to create a police sketch of a serial rapist. Elliott met with tow of the victims and asked the women detailed questions about their attacker’s appearance, sketching their responses: How far apart were his eyes, how high was his hairline, what was his mouth like? “It’s what I do while I’m working on a painting, but I just verbalized it,” she says. Her sketch turned out to be a good likeness. The rapist was caught.

When she began painting longhorns, Elliott’s talent and instincts for portraiture found a fresh focus. She saw them as individuals, with interesting bovine eyes and distinctive demeanors, worthy of the often large=scale paintings in which they appear against backdrops of gorgeous Texas skies. Her placid longhorns reflect the relative simplicity of the bovine world. “I always like the sense of community with livestock animals. To be in a pasture with that is really comforting.” Elliott says.

As curator of the Coors Western art show, publisher, and writer Rose Fedrick puts it: “She gives her subjects a sense of royalty, grace and power, and yet there’s also something wry about her paintings, as if she’s looking back and giving a wink to old Leonardo di Vinci.”

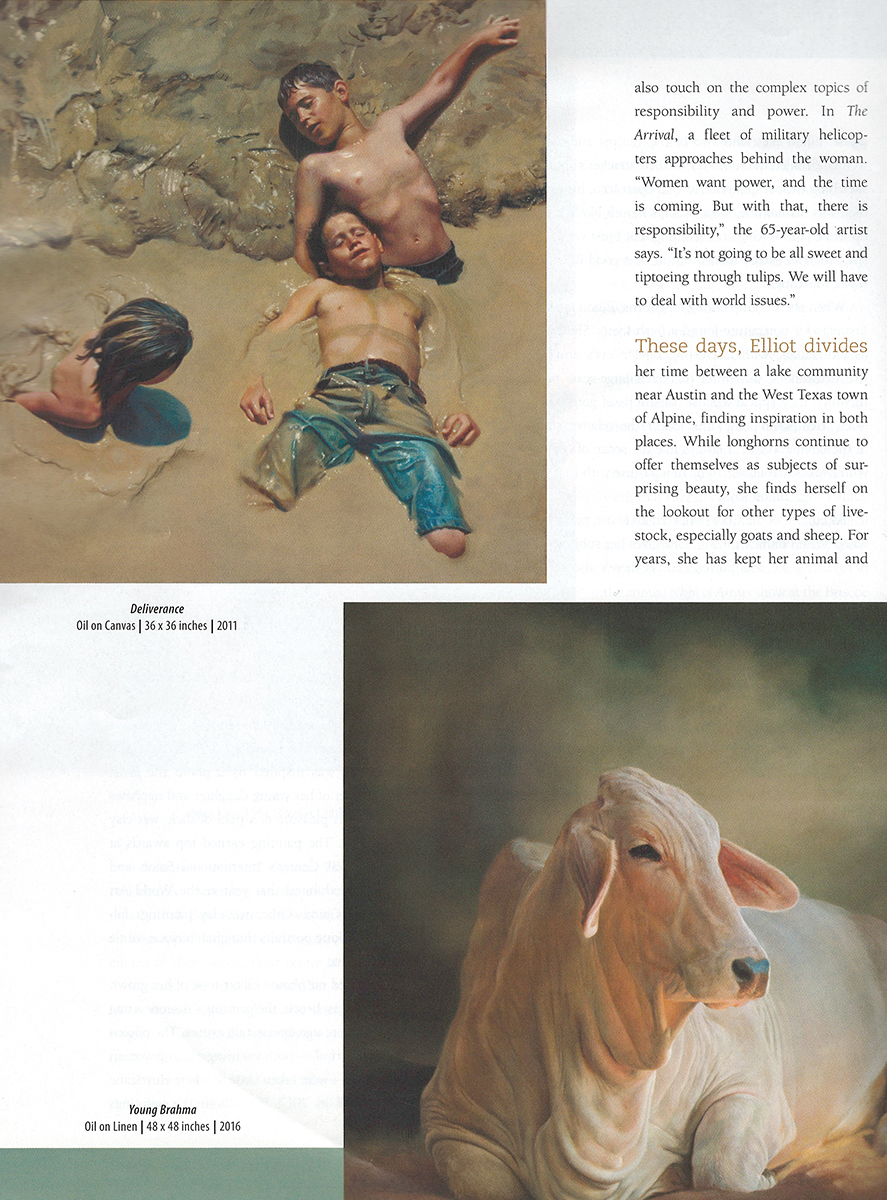

This reference to a Mona Lisa-like sense of intrigue also applies to Elliott’s figurative work. Her first large figurative painting, Deliverance, was inspired by a photo the artist had taken years earlier of her young daughter and nephews enjoying the luxurious pleasure of a pool of slick, wet clay under the Texas sun. The painting earned top awards at the 2012 Art Renewal Center’s International Solon and elsewhere, and was exhibited that year at the World Art Museum in Beijing, China. Other wet-clay paintings followed, along with striking portraits that often include subtle suggestions of narrative.

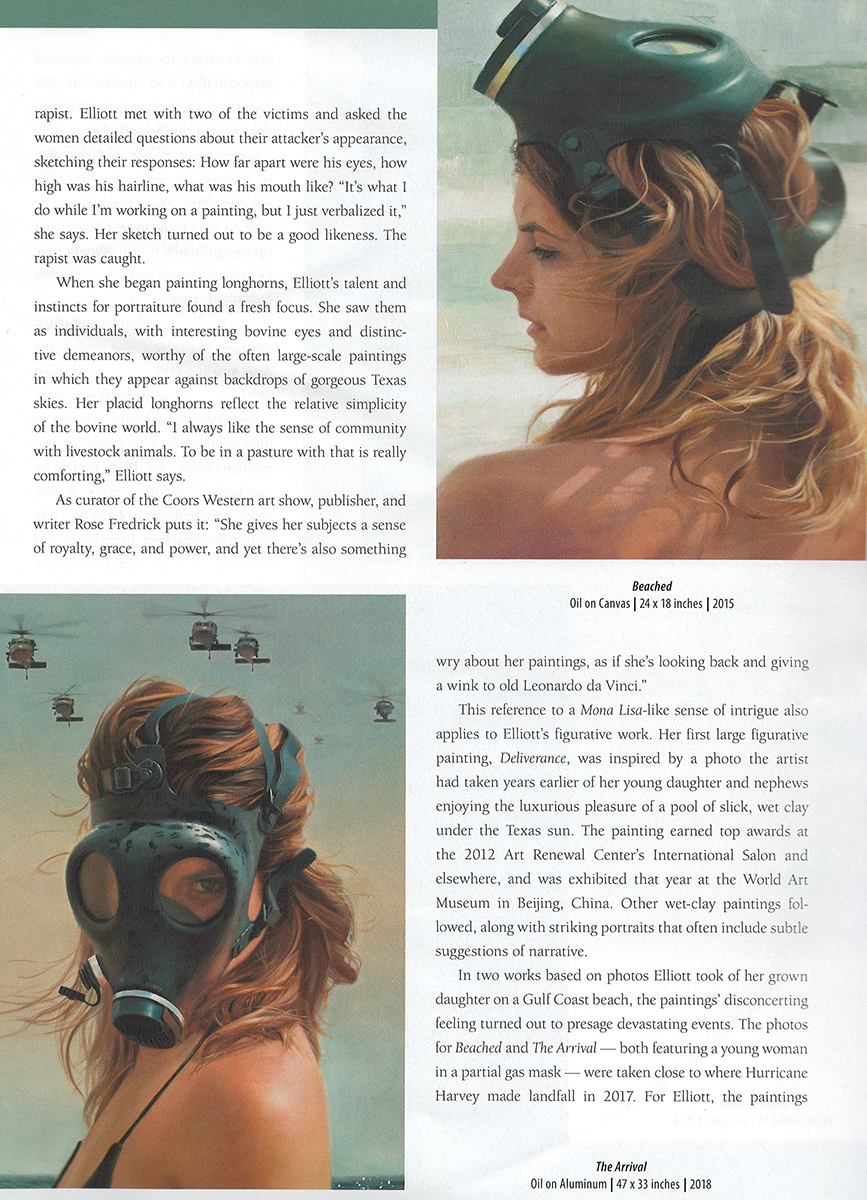

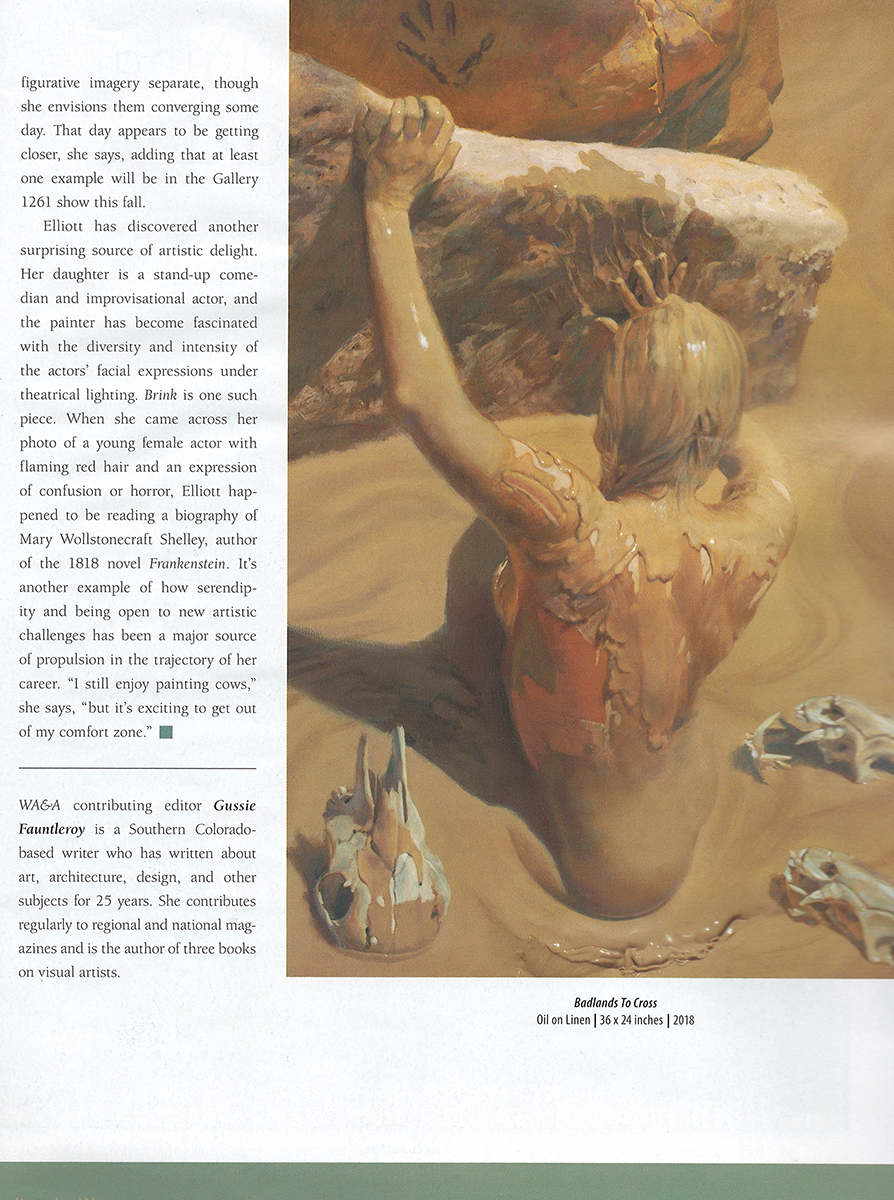

In two works based on photos Elliott took of her grown daughter on a Gulf Coast beach, the paintings’ disconcerting feeling turned out to presage devastating events. The photos for Beached and The Arrival — both featuring a young women in a partial gas mask — were taken close to where Hurricane Harvey made landfall in 2017. For Elliott, the paintings also touch on the complex topics of responsibility and power. In The Arrival, a fleet of military helicopters approaches behind the woman. “Women want power, and the time is coming. But with that, there is responsibility.” the 65-year-old artist says. :It’s not going to be all sweet and tiptoeing through tulips. We will to deal with world issues.”

These days, Elliot divides her time between a lake community near Austin and the West Texas town of Alpine, finding inspiration in both places. While longhorns continue to offer themselves as subjects of surprising beauty, she finds herself on the lookout for other types of livestock, especially goats and sheep. For years, she has kept her animal and figurative imagery separate, though she envisions them converging some day. That day appears to getting closer, she says, adding that at least one example will be in the Gallery 1261 show this fall.

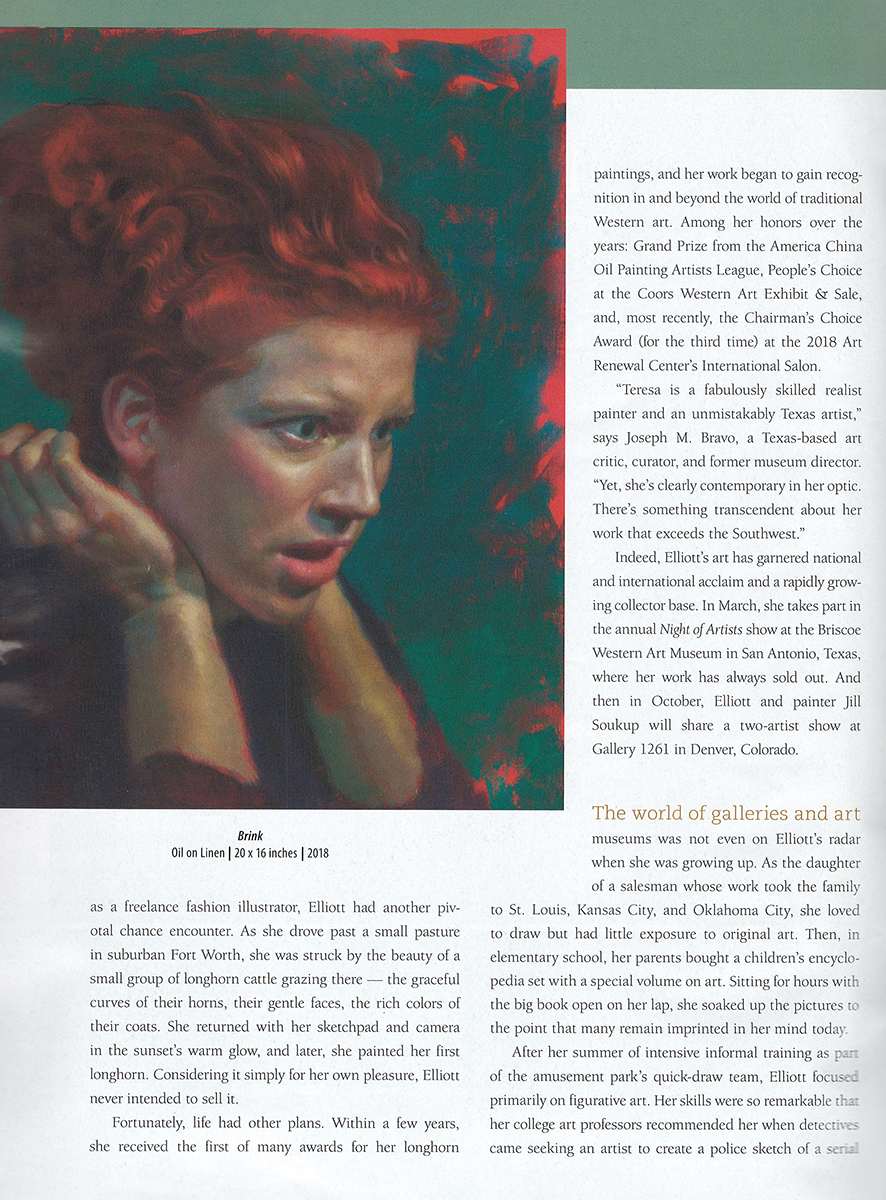

Elliott has discovered another surprising source of artistic delight,. Her daughter is a stand-up comedian and improvisational actor, and the painter has become fascinated with the diversity and intensity of a the actors’ facial expressions under theatrical lighting. Brink is one such piece. When she came across her photo of a young female actors with flaming red hair and an expression of confusion or horror, Elliott happened to be reading a biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of the 1919 novel Frankenstein. It’s another example of how serendipity and being open to new artistic challengers has been a major source of propulsion in the trajectory of her career, “I still enjoy painting cows,” she says, “But it’s exciting to get out of my comfort zone.”

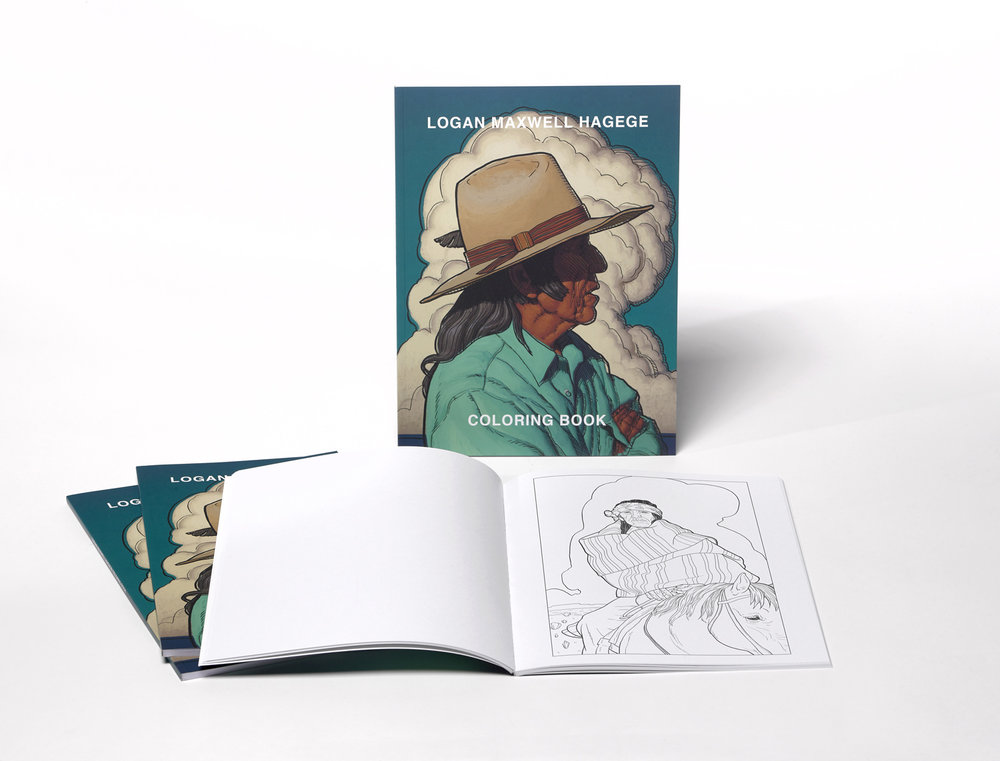

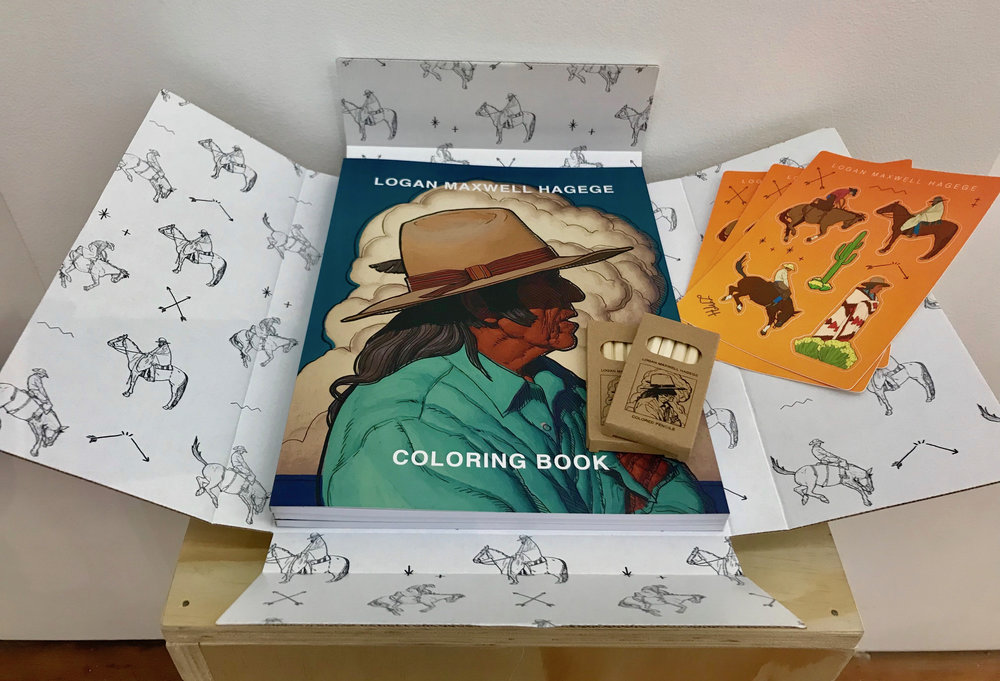

Logan Maxwell Hagege Coloring Books

Logan Maxwell Hagege Coloring Book released on Saturday December 1, 2018 at 11am PST exclusively on MaxwellAlexanderGallery.com/shop/

The book includes 25 images based on original paintings by Logan Maxwell Hagege. All pictures were recreated by the artist himself to insure quality images on each page.